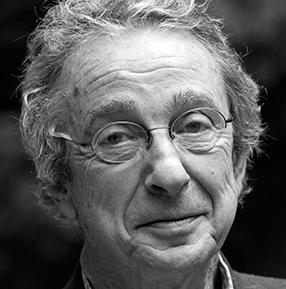

Michael N. McGregor, author and professor of creative writing in the Department of English at Portland State University, published a biography in September 2015 titled Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax. The book chronicles Lax’s life and his career as a poet. It also explores some of the important relationships Lax had—with God, with Thomas Merton, with a family of circus performers, and with McGregor himself.

McGregor has been associated with the Collegeville Institute since 2009. He spent a semester in residence in the fall of 2011, and has taught several writing workshops over the years. Betsy Johnson-Miller spoke with Michael about his book when he was in Collegeville for a three-day author residency.

You wrote this book, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax, at least in part, as a result of meeting Robert Lax. Would you have written this biography if you hadn’t met Lax in person?

It was the presence of the man and getting to know him that intrigued me. I wanted to uncover more of the details of his life. I never expected to write a biography, and I’m not sure I would have written this if I’d just encountered his writing or even things about him.

Could you give us a sense of his presence?

To be in his presence was to feel loved, delighted, and completely accepted.

In the book, I talk about how he described Thomas Merton with only one word: liveliness. And that’s what I would say about Lax as well. When I met him, he was 69, and that’s an age when many people do not have a lot of liveliness left. But he was delightfully lively. He was, in many ways, childlike, and to be in his presence was to feel loved, delighted, and completely accepted.

Is it what he said? Or how he looked at the world?

Lax was lively in his manner and how he treated people. He would often say, “Yes, yes,” or “Good, good.” Those were his favorite phrases, and he was always encouraging people to say what they had to say, to express themselves, or in my case, to write things down. He would often break our conversations and say, “Write that down, write that down.” Sometimes, when he felt someone especially needed encouragement, he would say, “Well, that reminds me of Merton.” He may have meant it, but he also may have been thinking, “This person needs encouragement, so let me compare you to this friend of mine who is amazing.”

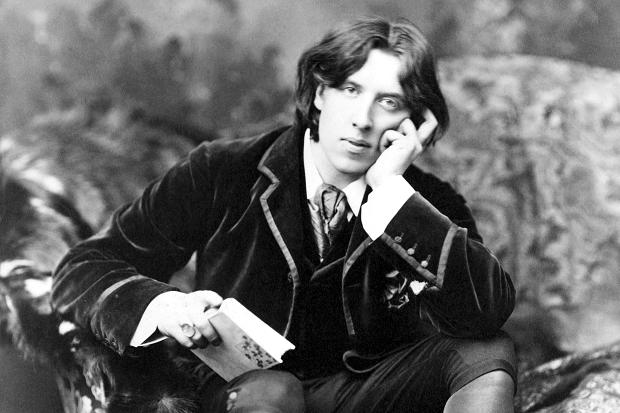

Lax had a deep and abiding friendship with Thomas Merton that impacted both of their lives. Merton became a monk, whereas Lax did not. Would you say they both led holy lives?

When we talk about a holy person, we are in danger of over-spiritualizing. We start to think of someone as not meant for this world. That is not the case with Lax. He was fully alive as a human being. He was of this world, but at the same time, he was fully attending to the living God, and he was fully alive as a human being to the people around him, and to himself. Merton and Lax were very different people personality-wise. They had different gifts, different ways they were tuned. But they both had a thirst for God that was their primary characteristic.

How would Lax describe the act of writing?

Lax would not have separated writing from living. He was always trying to get at what his soul was saying to itself. He believed that “down there” was where God speaks to us, from inside of us, at our deepest core. So, writing was a sacred act, but so was living. For Lax, every breath was a holy thing.

Should we consider Lax an exemplar? In other words, should we as people or as writers try to live like he lived?

Lax would never have said, “Live like me.” In fact, if you started to suggest you were going to emulate him, it would have made him very nervous. Except he did want people to emulate him in this way—to love, to be as close to pure love as you could be. It wasn’t important for him what your circumstances were or what you pursued, as long as you pursued it out of love.

There’s a story in the book about a young man going fishing. Lax believed if that man wants to go fishing instead of caring for his grandmother, if he’s not caring for her out of love, then it’s better for him to go fishing. Because he should do what he does out of love. That was how Lax saw life.

One of his most important characteristics—embracing poverty—unleashed a great deal of energy and time in his life. He might talk to you about it, but he wouldn’t say, “You have to do this—live this same way.” Some people called him a guru. I don’t. Gurus tend to give you ways to live and are much more prescriptive about that, and he was never prescriptive. For Lax, what was important was to put ourselves in a place where grace can flow, because once we do that, then things start happening. He also believed very strongly that everybody desires God, and the more we can recognize and act on that desire, the more things will take care of themselves.

As a writer yourself, how did Lax’s thoughts on writing influence you?

What Lax said was that you should write what you want to write and then try to say it as well as you can.

The most important thing that he unlocked for me as a writer was the idea that I should write about the things that are mine to write about and that I care about. As a young writer, it’s easy to get all these ideas, or think “I want to be in this magazine, so I should write this.” What Lax said was that you should write what you want to write and then try to say it as well as you can. More importantly, he believed you should write for yourself first and only, really. He said that if an editor gets to see that writing, he should consider himself lucky.

It’s a very different way than we are taught to think about writing. We’re taught to think that we’ve got to do these things to get people to print our work. Lax believed strongly that as a writer, if that’s the thing you are called to do, then your job is to write what you are interested in as well as you can and try to get closer and closer to a kind of truth in that. If that happens, then the publication part will take care of itself.

Many writers are known for their edgy lives, whether in terms of sexual behavior or alcoholism or drugs. Lax falls at the opposite end of the spectrum. What do you make of that dynamic, both in terms of Lax himself, and of writers and writing in general?

Some people look at the lifestyles of legends like Fitzgerald and Hemingway and think, “Oh, that’s how you become a good writer,” rather than thinking “these good writers did stupid things that eventually impaired their writing instead of enhancing it.”

The best example of this from Lax’s life is the difference between him and Jack Kerouac. They were friends right around the time On the Road came out. This was a high point of Kerouac’s life as a writer in many ways, and there was this moment when Kerouac was going to follow Lax to live in a spiritual community outside of Paris. Lax went first, but Kerouac never joined him. He wrote Lax a letter that basically said, “Bob, I’m not coming. That’s the kind of thing I need to get away from,” and he turned to Buddhism instead. Even more than that—and Kerouac’s honest about it in the letter—he turned to women and drink, and the life destroyed him. And the same thing happened to others—like Dylan Thomas—who were in Lax’s life as well.

Lax said that the best gift you can give to other people is to take care of yourself.

Over time, Lax developed this sense that we need to take care of ourselves, and that doing so allows us to do our best for other people, for our writing, for whatever. Late in life he said that the best gift you can give to other people is to take care of yourself, even physically. Some writers think that they have to be where the buzz is, that they have to be in there, moving and doing things. Lax felt that the buzz he was interested in was inside himself.

Is there a moment with Lax that has stayed with you?

One such moment is when he signed one of his books and gave it to me. Inside it read, “There’s not much difference between us.” Another was toward the end of his life when he told me, “I had a dream last night that you said to me, ‘Peace is a good thing to seek, and love does conquer all.’” The second one in particular felt like a charge to me in a way. I don’t think he meant it that way. I think it was more of a hopeful thought, a hopeful dream for him, but I certainly go back to it and think, “Yes, I want to be that person and always doing that.”