I found this article while going through some old papers recently. Poets & Writers Magazine commissioned me to write it ten years ago but never ran it. So it’s appearing here for the first time. I hope you enjoy it.

The Patient Novelist

© Michael N. McGregor, 2011

There are dozens of books about it but none reveal how crippling it can be or the worst of its many symptoms, the most secret one: the shame. Evasion and deflection become part of your personality. You begin to answer questions with a single syllable or a vacant stare, until the questions stop.

I’m talking, of course, about the itch to write a novel and the sad results of scratching it for those who don’t find early publication: the seemingly stillborn body hidden in a lower drawer.

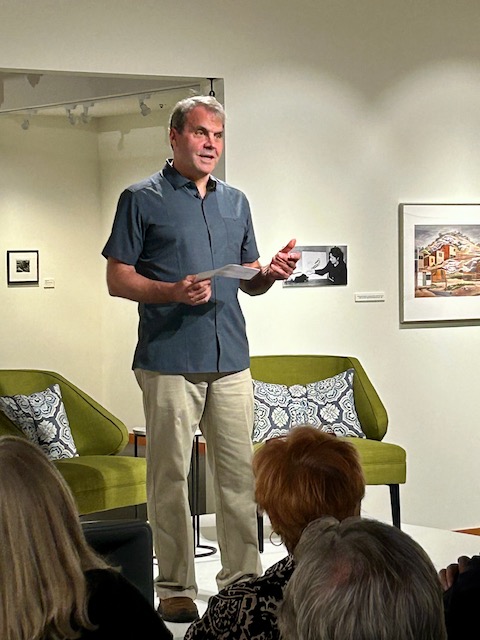

“I didn’t ever tell anybody about it,” says Selden Edwards, who felt the itch while earning a master’s degree at Stanford; for the next 30 years he stayed in his hotel room whenever his family went to a museum or the beach. “My children knew I had it but they’d never read it. My wife is an avid reader and she’d never read it. Two years ago if I’d invited everyone I ever cared about to a huge party and stood up and mentioned the name Wheeler Burden, nobody in the room would have known what I was talking about.”

Wheeler Burden is the time-traveling, baseball-whizzing, guitar-playing hero of The Little Book, Edwards’ first novel, a project he worked on surreptitiously for most of his adult life, discarding it and picking it up again half a dozen times before Dutton bought it for a high six-figure sum in 2007.

When that happened, “a big hole opened in the heavens,” Edwards says. “I was going to have a novel published. It was the dream of a lifetime.”

The dream of a lifetime might seem a bit clichéd but for Edwards it was literally true. Although he served as a prep school headmaster for 25 years and raised three healthy and successful children, he refers to The Little Book as his life’s work.

“I must admit it didn’t feel like that when I was working on it,” he says. “It was just this frustrating thing I had. I didn’t think of it as very meaningful.”

Even so, over the years he put everything he knew or learned into it, adding complications and connections, thickening the characterizations and plot.

“When you work on a story that long,” he says, “you come up with little details and you say, ‘I can work that in,’ or someone tells you a good story and you think, ‘Oooh, I could put that in.’ I could do a footnoted version of my novel that would be four times as long. Almost every detail comes from some part of my life.”

The list of authors who’ve suffered the vicissitudes and felt the significance of prolonged labor on a single novel is longer and more distinguished than you might think: Malcolm Lowry spent a decade writing and revising his most famous work, Under the Volcano; Katherine Anne Porter took two decades to write her single novel, Ship of Fools; Jean Rhys produced parts of her post-colonialist classic, Wide Sargasso Sea, over almost thirty years; and Ralph Ellison struggled so long to write a second novel after the phenomenal success of Invisible Man—forty years!—he never finished it.

Unlike Edwards, these authors all had agents and advocates, readers and reputations. So why did they work on a single book for so long? What did they gain by sticking with it rather than moving on?

Nothing in our culture encourages anyone to write a novel, let alone work on it for decades. Talented fiction writers whose first novels don’t sell right away are like those old Olympic hopefuls who had to fend for themselves while their foreign competitors received government support. More often than not, agents (if you can get one) will send your novel to no more than a handful of publishers before giving up. If the rejections point to a clearly fixable problem, they might risk a second round; if not, you’re on your own to wonder whether your book is fatally flawed or just not salable in its current condition—whether you should burn it or stick with it, filling it with all you know.

Lowry chose the second course with Under the Volcano, a novel so packed with meanings and allusions some critics have called it unreadable while others have proclaimed it one of the best books of all time. (In 1998 the Modern Library editorial board put it at #11 on their list of the 20th century’s 100 Best Novels in English. James Joyce’s 18-year-effort Finnegans Wake was #77 and Ulysses, which took him seven years, was #1.)

Lowery wrote three full drafts between 1936 and December of 1940 when his agent sent his manuscript to four publishers who all rejected it. Nine more would turn it down in the months ahead. By then, however, Lowry was already working on a fourth draft in which he revised each of the book’s twelve chapters at least four more times.

“This is not to say that Under the Volcano became longer,” writes Lowry biographer Douglas Day, “it did not. It became denser, as [Lowry] applied quick, small pieces of information and insight here and there, in masterfully controlled profusion.”

The result? British publisher Jonathan Cape published the book in 1946 but only after Lowry wrote an impassioned response to a reader’s report that “with surprising consistency…condemned exactly what supporters of Under the Volcano have found great in it.”

Rejection and lack of understanding aren’t the only reasons for an author to spend decades on a single book. Porter’s delay in finishing her one novel—a wide-ranging yet intimate look at the lives of several dozen people sailing from Mexico to Germany on the eve of Hitler’s rise—had less to do with others’ opinions than with scope. Porter was already well known as a short story writer; any number of publishers would have been happy to bring out her longer work. But she was trying, as biographer Joan Givner writes, “to work on a huge panoramic canvas and solve the riddle of what had gone wrong with the whole Western world in the twentieth century.” Not an easy task for someone used to writing short—or someone working in today’s less-patient publishing environment.

According to another biographer, Darlene Harbour Unrue, Ship of Fools “represents the final stage of Porter’s thematic and stylistic evolution. On the ship are versions of earlier characters she created or planned to create: in the narrative are scenes that mirror scenes from her other stories, short novels, and essays; themes treated in the shorter work are treated again in the long novel; and the prose medium of the long novel is a combination of stylistic techniques that served her well in the other pieces.”

In other words, the novel Porter labored over for so long became her life’s work.

Like Porter, Jean Rhys had a strong publishing history (four novels, a book of short stories and several autobiographical pieces) when she began working on what eventually became Wide Sargasso Sea (#94 on the Modern Library list) sometime in the late 1930s. In a fit of anger in the mid-1940s she burned her half-finished manuscript. She wouldn’t work on it again until 1958 or finish it until 1966 but she never stopped thinking about the Caribbean childhood on which it was based. Finally, in 1964, after a quarter century of brooding, the book came together when she wrote a poem.

“Even when I knew I had to write the book,” she wrote to her publisher, Francis Wyndham, “still it did not click into place—that is one reason (though only one) why I was so long. It didn’t click. It wasn’t there. However I tried.

“Only when I wrote this poem—then it clicked—and all was there and always had been.”

That clicking never came for Ellison who published two books of essays and miscellaneous works but never completed his long-anticipated second novel. His literary executor, John. F. Callahan, suggests that the scope of Ellison’s vision—his attempt to write his own ‘life’s work’ (as if Invisible Man, #19 on the Modern Library list, weren’t enough)—may have been the reason. In his introduction to Juneteenth, the novel he assembled from manuscripts Ellison left behind, Callahan writes: “Sometimes revising, sometimes reconceiving, sometimes writing entirely new passages into an oft-reworked scene, he accumulated some two thousand pages of typescripts and printouts by the time of his death.”

As early as 1968 Ellison’s struggle to write his follow-up novel (he had written 1,000 pages already) was causing him frustration, anxiety and, yes, shame. “He has become so embarrassed about his inability to finish the book,” wrote critic Richard Kostelanetz, “that he gets visibly upset when acquaintances ask about it.”

(If you’re wondering what Ellison wrote in all those pages Callahan mentions, Modern Library published over a thousand of them under the title Three Days Before the Shooting in 2010.)

So what do you do if you’ve written a novel, sent it out and either failed to find an agent or found one who wasn’t able to sell your book? Most writers move on to other projects. Some quit writing altogether, either permanently or temporarily, by choice or from necessity. A very few love their project enough, are confident (or maybe crazy) enough, and have patience and vision enough to start again with the same book, putting more of themselves and their time into it, risking making it their life’s work.

“It’s a manic-depressive practice,” Edwards says, “because when you’re in the heat of revising you start thinking, ‘Oh, boy, this is getting good,’ but then you get those cold hard rejection slips. I had a paycheck so I wasn’t desperate, but each time I got rejected I felt ready to give up.”

The darkest days came near the end when he’d retired and had the time to do one more complete revision in a relatively short amount of time. He sent the results to nine agents. “The unbelievable thing,” he says, “is that it was maybe 80% of what became the final book and every agent rejected it unceremoniously, with just a printed rejection slip.”

Once again, however, Edwards started over, this time hiring a freelance editor who helped fix his ending and several smaller problems. They worked together for a year. One week after they stopped, Edwards had an agent. Two weeks later, he had a contract. One year after that, he had a bestseller.

“When the agent called, he said, ‘You haven’t given this to anybody else, have you?’” Edwards remembers with a laugh. “‘I have to represent this book!’

“One of the things you try to do as a mature person is not evaluate yourself based on the opinion of others. You try to have your own integrity. But when you’re a writer it’s almost impossible to do that. The key thing in working with the editor was that he said right away, ‘This thing has promise.’ He was the first person to read it from cover to cover. That was the whole difference.”

Edwards is about to publish his second novel—a book he sold in two days with just a proposal: “They said, ‘Can you do this thing in a year?’ and I said, ‘Yes, I can.’”

What advice does he have for others willing to stick with one book over time?

“Number one, don’t give up. But be realistic about it. Maybe you’re going to write a lot and it’s never going to be published. Just because it happened for me doesn’t mean it’s more likely. The other thing is always finish a draft. Every draft I wrote was about twice as good as the one before. I kept finishing and that made a huge difference.”

“You know,” he adds, “I’ve had a lot of good stuff in my life, but I wanted to have a novel from the time I was a young man. All that’s going on now—having a bestseller and all—it’s like being drafted by the Celtics. It’s just an unbelievable dream and I live it every day.”

* To learn more about Selden Edwards, including the response to his follow-up novel, The Lost Prince, visit his Wikipedia page.