I’ve added quite a few events to my appearance schedule in recent weeks. Check the Talks page for a full list. If you’d like to discuss a possible talk or reading in your area, please contact me using the Contact form on the About page.

Latest Posts

-

I’ll Be a Visiting Professor at St. Bonaventure University in March

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve been selected to be the Spring 2017 Lenna Endowed Visiting Professor at St. Bonaventure University in Olean, New York. I’ll be on campus for the last two weeks of March, giving talks, visiting classrooms, meeting with students, and chatting with the Franciscan friars.

I’m especially honored to receive the Lenna Professorship because the first recipient of it, when it was established in 1990, was Robert Lax. St. Bonaventure is in his home town and, as those who’ve read my biography of him know, he and his mother went there often. The friars were an important early spiritual influence on him.

The dates for the public talks haven’t been set yet but they should be soon. I’ll post them in the Talks section of my website. If you’re in the area, I hope you’ll come!

-

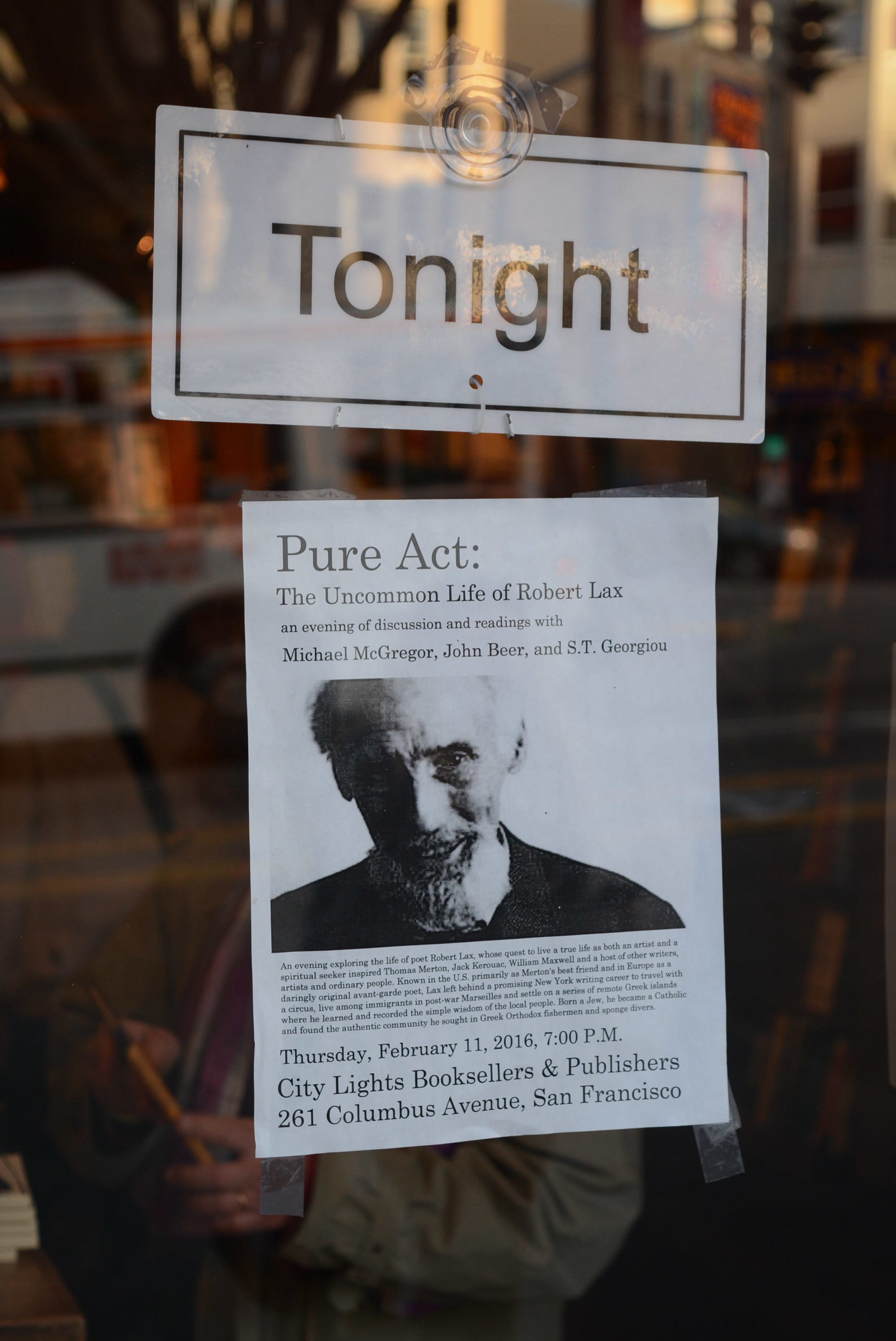

Video of Fordham Editor Talking About the Acquisition, Design and Selling of PURE ACT

I didn’t know this was available online but found it yesterday: It’s a video of my editor, Fred Nachbaur, talking about the acquisition, design and selling of my book, PURE ACT: THE UNCOMMON LIFE OF ROBERT LAX. It was presented at a conference as an illustration of what university presses can do beyond their usual markets:

-

A Year of Pure Act

The image here is of the bottle of vintage French wine Sylvia and I opened to celebrate signing my book contract with Fordham University Press two years ago. Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax has been out in the world just over a year now, and what a year it has been. The unofficial end of the book’s debut year came three weeks ago when we attended the Washington State Book Awards in Seattle. Pure Act was a finalist in the Biography/Memoir category. It didn’t win but it was a great honor to be recognized in my home state.

All told, Pure Act was a finalist for four awards: the WSBA in Biography/Memoir, the Religion Newswriters Association Book Award for best religion book of the year, the Association of Catholic Publishers’ Excellence in Publishing Award in Biography (it won second place) and the Catholic Press Association’s Book Award in Biography (it received an Honorable Mention). It has been nominated for an Oregon Book Award too, but the finalists for that won’t be announced until early January 2017.

For a big book by a first-time author about a little-known poet published by a small publisher, it has done pretty well. It’s in its third printing and a paperback version will be published in March 2017. It was favorably reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, the Times Literary Supplement in the U.K., Publishers Weekly, the Oregonian and over 20 other publications. The American Association of University Professors recommended it as one of ten nonfiction books and only two biographies (the other was of Mark Twain) in the area of American Studies for libraries to purchase in 2016. I’ve had a chance to read from it at bookstores, universities and community events across the country. And it has led to my being asked to be a keynote speaker at the 2017 International Thomas Merton Society conference at Saint Bonaventure University.

I’m reluctant to let this wonderful year end, but time marches on, of course, and I’ve already drafted my next book, a memoir about a year spent in the San Juan Islands. A huge thank you to all who were part of a marvelous experience.

-

PURE ACT a Finalist for a Washington State Book Award

Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax has been named a finalist for the Washington State Book Award in Biography/Memoir. You’ll find a full list of finalists and information about the awards ceremony here.

If you live in the Seattle area and are interested in attending, the awards ceremony will take place 7-9 p.m. in the Microsoft Auditorium at the Seattle Public Library’s central branch (1000 Fourth Avenue).

The ceremony is free and parking is $7 in the library garage. -

PURE ACT a Finalist for the Religion Newswriters Association 2016 Book Award

Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax has been named one of ten finalists for the Religion Newswriters Association’s 2016 Religion Nonfiction Book Award. A full listing of finalists for all awards is here. Winners will be announced on September 24.

-

PURE ACT Wins a 2016 Excellence in Publishing Award and NCR Reviews It

I learned this week that Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax has won a 2016 Excellence in Publishing Award from the Association of Catholic Publishers. It received second prize in Biography. First prize went to my good friend Angela Alaimo O’Donnell for her biography of Flannery O’Connor. The ACP announcement is here.

On the same day I learned about the award, a nice review of Pure Act by Dana Greene, biographer of Denise Levertov, appeared on the website of the National Catholic Reporter. You can read it here.

-

Using the “I” in Biography and Other Writing About Others

Two days ago I wrote about the use of biography in memoir. Today I want to address the use of memoir in biography—or, to be more exact, writing about others that includes the author as a character. This is done quite often in profile writing. Susan Orlean, for example, begins one of her best-known profiles, “The American Male at Age 10,” with a whimsical imagining of how things would be if she and her 10-year-old subject were to marry. (Spoiler alert: It ends with the boy slingshoting dog food at her butt). In many profiles, the author isn’t just an interviewer or chronicler; she’s part of the story.

The presence of the writer/interviewer is an expected feature of Q & A’s, of course. In the best of them, what we witness—what we enter into—is less an interview than a conversation, a give-and-take discussion between two intelligent people. Yes, the discussion leans toward the ideas and work of one of the two participants, but the interviewer plays a significant role, bringing not only her knowledge but also her thoughts and personality to the interaction.

Even so, there is a curious reluctance among biographers and critics to allow a biographer to appear in his narrative. One reviewer of my biography of Robert Lax took me to task for doing so, saying dismissively that I should have written a second book, a memoir, if I wanted to write about our relationship. A more respectful reviewer for a different publication suggested more delicately that “readers will differ as to whether the author’s injection of his own voice in the text adds to or distracts from his subject’s life story.”

Yet it seemed false to leave myself out of a book about a man I’d known well for 15 years, and I took pains to do all of the research any biographer would do to write the full story of Lax’s life. In fact, those same reviewers who questioned my presence in the text praised the extensiveness of my research. I felt—and many readers (and reviewers) have agreed—that my intimate knowledge of my subject allowed me to bring him more fully to life. The New York Times’ reviewer, in fact, called my “memoir” sections “vivid and engaging.” Which shouldn’t be surprising, of course, since they came from direct observation and experience rather than a piecing together of quotes from letters and interviews.

It strikes me as strange that an author’s personal account would be denigrated when biographers regularly use any and all writings in which other people describe encounters with their subjects. I can understand the suspicion that writing about someone you knew well and even admired might prejudice your account. And there are any number of questionable biographies written by members of a subject’s inner circle—biographies that betray an agenda. But why would use of the “I” or first-person observation indicate an agenda or hidden bias any more than any other way of writing about a person? Hackwork is hackwork, whatever its point of view.

And there is a point of view in biography, whether acknowledged or not. In recent decades, nonfiction writers, in general, have abandoned the so-called “objective” approach to writing about their subjects, recognizing that all writing is subjective, influenced not only by one’s particular experiences and education but also gender, class, race, sexual orientation, national origin, philosophy, creed, etc.

Despite this more general awareness in nonfiction writing, biographers continue to write in—and in many cases, insist on—a mostly Victorian style, composing their cradle-to-grave narratives as if taking dictation from God—as if the story they’re telling about their subject is simply fact-based truth. In his book How to Write Biography: A Primer, for example, Nigel Hamilton, who fills his pages with all kinds of good advice for first-time biographers, never discusses the possibility of using the “I,” except when castigating Edmund Morris for injecting a fake “I” into his biography of Ronald Reagan.

What is most curious of all, perhaps, is that virtually all biographers praise a book in which the “I”—and, to some extent, memoir—figures prominently: James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson. One of the main things they praise, in fact, is how fully Boswell brings his friend to life by describing Johnson as he knew him, relating words Johnson said in his presence, and showing Johnson in scenes he witnessed. In my copy of Boswell’s book, 242 pages cover Johnson’s 54 years of life before Boswell met him (when Johnson was 54) and 1,001 pages are about the 21 years Boswell knew him. In other words, 4/5 of the book is drawn, to a large extent, from Boswell’s personal relationship with his subject, rendered in text peppered with Boswell’s “I.”

There are biographers who use the “I,” of course—even extreme prejudice among peers against a particular technique can’t keep some brave souls from employing it. When J.D. Salinger kept would-be biographer Ian Hamilton from using quotes from his letters and interviewing people close to him, Hamilton turned his book into a search for knowledge about his subject, “incorporating within it,” as the book’s jacket copy says, “his own sometimes poignant, sometimes comic, sometimes exasperating quest for Salinger.”

The researching and writing of any biography is a quest. A personal endeavor. Not every biography has to include the details of that quest, but there’s no good reason why a biography shouldn’t either. A biography is a story, an encounter, a vision and version of a person’s life. I, for one, enjoy when a biographer like A.J.A. Symons, in his book The Quest for Corvo, takes me along on the researching adventure, using whatever material will best engage me and bring his story most vividly to life.

-

Memoir Monday #6 — What Do We Owe the People We Write About When We Write Our Own Stories?

I suppose I should admit that my “experiment” has been a failure. I set out to post one blog entry a week on memoir writing and one on writing about others during the months of April and May. I haven’t written about writing about others for two weeks and this week my Memoir Monday entry is two days late. As I often say to students, life trumps writing. Work, illness and family matters interfere with our best-laid plans.

Maybe it’s appropriate then that today’s entry is about both memoir writing and writing about others—or, more accurately, writing about others in memoir writing. This may be the least-discussed aspect of memoir writing. We teach budding memoirists to examine their lives, to separate the contemplating consciousness from that of their earlier self, to dare to go deeper into pain and shame, but we don’t talk enough about how they should think about writing about the others in their lives.

In many memoirs, family members and others who have had relationships with the writer end up as collateral damage. Parents bear the brunt of the character blows. Sometimes they are the heroes of memoirs but more often they are the villains. They are portrayed as drunk or drug-addled, abusive or negligent. Some are psychotic, some autocratic, and some narcissistic in the extreme. The scars left by their behaviors are real and, judging by what many memoirists have written, they are life-altering, character-warping, ineradicable even with therapy.

But memoir writing can inflict damage and leave scars too. This coming week my Memoir Writing students will read essays from a book called Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family, edited by Joy Castro. Some of the essays make clear how wounding words and stories can be. Others talk about the usefulness of letting family members read what has been written about them in advance of publication. All of them, in one way or another, raise the questions What do we owe the people we write about when seeking to write our own stories? and How can we make sure we’re being fair to others as well as ourselves?

There are no easy answers, of course. But the book my students read this last week, John Edgar Wideman’s Brothers and Keepers, suggests some approaches. Wideman’s book looks at the differences and similarities between himself, a widely respected writer and professor, and his brother Robby, who is serving a life sentence for his participation in a robbery in which a man was killed. The book is, in essence, a biography as well as a memoir, and the sections on Robby are based on interviews Wideman did with his brother. But Wideman goes to great lengths to show that he bears sole responsibility for what the book says.

In his Author’s Note, Wideman tells us his book is a “mix of memory, imagination, feeling and fact.” Because he wasn’t able to use a tape recorder during his prison visits, he had only inadequate notes from his conversations with his brother. He used those notes in conjunction with his lifelong knowledge of Robby, their family, their neighborhood, and the societal conditions at play in the lives of young American black men to write from Robby’s perspective, giving Robby a voice in the book. The voice in these sections is a voice of the streets, using slang and informal patterns of speech. Wideman makes it clear to his readers that he has constructed this voice but tells us, too, that Robby has read and approved and, at times, corrected it. You might call it a collaborative voice, one writer’s attempt to write about someone else while giving that person the opportunity to make sure the depiction of him reflects his own understanding.

Even then, Wideman is careful to tell us that his picture of Robby (which he uses as a mirror to reflect an essential part of his own nature) is his picture—limited and fragmentary, warped by his own partial view and understanding. “There will necessarily be distance,” he writes, “vast discrepancy between any image I create and the mystery of all my brother is, was, can be.”

It is this mystery every memoir writer needs to keep in mind when writing about anyone, even herself. We know people only partially and our views are distorted by our own needs, desires, emotions and experiences. If we respect the mystery of others—all that we don’t know about their inner and outer lives—and try, in the process of examining our own lives, to see from their perspectives, we have a better chance of being fair to them on the page.

We need to remember, too, that including them in our story means using them and their stories for our own purposes. “Though I never intended to steal his story,” Wideman writes, “to appropriate it or exploit it, in a sense that’s what would happen once the book was published.”

“Don’t I have a right to tell my story?” someone will ask. “Of course you do” is the only appropriate response. But rarely are our stories ours alone. Each of us lives at the center of a vast web of associations and relationships, families and communities. Every movement we make reverberates down the web’s delicate filaments, risking rifts and detachments and damage we can’t even see. We need to move carefully and respectfully, weighing the possible ramifications—on ourselves as well as others—of everything we say and do.