I don’t know when I first put spiritual and quest together. In my childhood church the word spiritual was seldom used, so I never thought about it. It took on meaning when I heard it spoken in the plural, applied to moving songs by enslaved people. It still bears that soul-deep sound for me, the suffering and longing for freedom.

Quest, I’m sure, came first through knights and Argonauts, the tales and myths of boyhood. While spiritual sounds softer, more ethereal, quest suggests a hardy physical journey, a dauntless searching through the material world. It’s the joining of these elements—the soft and hard, the hidden and the tangible—that gives the term spiritual quest a holistic feel, a sense that it involves one’s whole being.

I was well into writing my biography of poet Robert Lax before I realized that it was the story of a spiritual quest. This realization got me thinking about the books that influenced me when I was young, most of which, I found, had spiritual quests at their core.

The first that came to mind was Walden, which I first read in high school. It made me want to homestead in the Canadian woods just north of my Seattle home. I don’t remember Thoreau calling his solitary living a spiritual quest, but his book is full of things described in holy ways: the woods, the lake, the west. The benefits of simple living. His quest was for a way to live that kept him in the moment and in nature. His physical movement was small—a short walk from his Concord home—but he roamed continents in his thoughts, explored exotic lands within his soul.

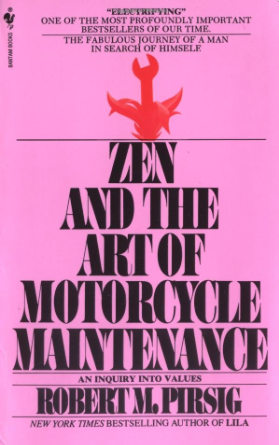

The second book I thought of—Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance—is more focused on movement, in this case a motorcycle ride, but that movement is even less necessary in terms of getting places than Thoreau’s walk from Concord. What’s more important for Pirsig is being away from one’s regular routine, out where paying close attention is both possible and needed. There, a mindful focus on the seemingly mundane unlocks his narrator’s thoughts about the Greek ideal of Quality, a value he finds lacking in the modern world.

I’m a bit embarrassed to reveal the third book that came to me, The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham, because I’m not sure I read it. It’s possible I only saw the Bill Murray movie. In the film, Murray plays a man who returns from World War I traumatized by his experiences. He rejects the regular life offered him and sets off on a quest for meaning. His quest takes him through the things that matter to other people, all the ways they seek fulfillment, including books. In the scene I remember most, he sits outside, alone and cold, somewhere in Asia, feeding pages from a suddenly useless book into a warming fire. He has realized that what gives life meaning is ineffable.

Two other books that came to mind don’t describe journeys per se. Not chosen ones, at least. One is Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which he explores the psychological states of Holocaust victims. A Holocaust survivor himself, Frankl finds that the survivors’ most important trait was the understanding that in any circumstance, no matter how dire, we retain the freedom to choose our attitude toward it.

The other book is James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, a collection of essays drawn from Baldwin’s life that echo Frankl’s thinking. Instead of focusing only on the individual, though, Baldwin looks at our society. Not only do we have the ability to choose our attitudes, he says, but the choices we make determine our common future. The quest implied in both these books is to become a person who can make what are, in essence, spiritual choices.

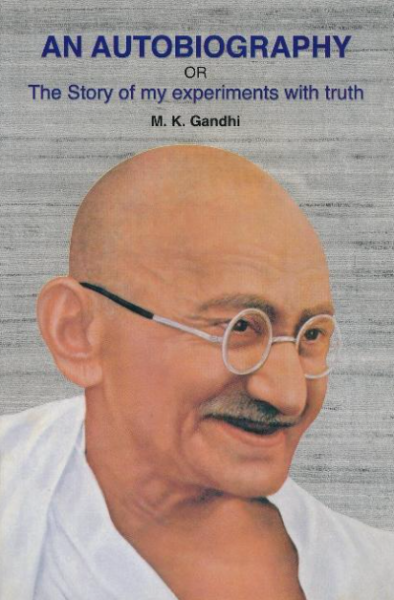

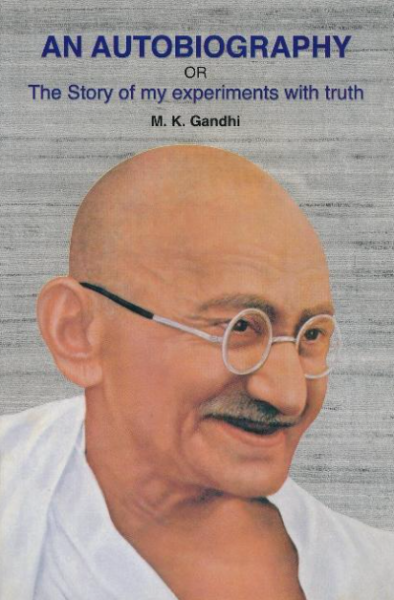

The last three books I thought of are all a type of spiritual autobiography and so, I guess, more truly fit the category: Gandhi’s The Story of My Experiments with Truth, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain (in which I first encountered Robert Lax).

I found Gandhi’s book tedious in places but his story of becoming sensitized to the world’s needs through experiences of prejudice and encounters with the less fortunate inspired me to pursue more of these encounters myself. Once again, my memory of a book has been altered by a movie. Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi” shows him riding through India in a third-class train car to learn about the life of the common people. In the scene I remember most, he sits in his homespun clothes, still and aware, absorbing the noise and chaos of the lives around him rather than fleeing. It is this acceptance of the moment, his poorer countrymen’s reality, that allows Gandhi to transcend his privilege and become a true leader.

Malcolm X’s book is even more clearly about the struggle with one’s self as well as with society. In many ways it is the most extraordinary book on this list because Malcolm X had only his own awareness and fire to change him from an angry hustler for whom racial oppression is a given into a touchstone for whites as well as blacks, an evolving consciousness enlarged by his mistakes as well as his triumphs.

Merton’s book is the one that most emphasizes the spiritual. It’s tempting to say that he had fewer physical things to struggle against—he wasn’t a victim of racism or a Holocaust survivor; he didn’t have the mental problems of Pirsig’s narrator or the horrifying memories of Maugham’s hero—yet Merton was aware that his main struggle was against his worldly self: his complacency, his egoism, his misplaced desires. Nothing outside his own consciousness forced him to confront himself and the life he was living. Yet he was willing to relinquish everything to find the meaning he desired, to reject all physical comfort in pursuit of a purely spiritual good.

So what has been the benefit of reading these books? Awareness, I suppose. Increased sensitivity. And camaraderie across the ages: a feeling that I’m not alone in my own spiritual pursuits. These fellow seekers give me courage and models to remember when my own struggles, however comparatively small, sometimes seem too much.

Michael N. McGregor is the author of the new biography Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax (Fordham University Press, 2015) . A former journalist and editor, he is a professor of English and Creative Writing at Portland State University.

The photograph used at the beginning of this post was taken by Michael McGregor.